When you’re as old as Altgeld Hall, you deserve a nice cleansing scrub. The stony skin of the building dates to as far back as 1896, after all, and a lot of history, and other gunk, has built up on the stone.

Even a U of I student’s thesis from more than 50 years ago notes the coloration change. Muriel Schienman (MA, '69; PhD, '81; art history), in her 1969 master’s thesis, “Altgeld Hall, The Original Library Building at the University of Illinois: Its History, Architecture and Art,” wrote the following:

“Roughly hewn, randomly placed hard pink sandstone form the Kettle River quarry in Minnesota was used–and probably very effectively in contrast to the red tile roof–but weathering and grime have changed the color to more of a greyed-buff. The richly textured stone catches light and shade and creates an animated surface, a significant element for the facade of the building which has sunlight only in the very early spring.”

The scrubdown comes as part of an overhaul to the interior and exterior of Altgeld. Masonry cleaning, stone repairs and repointing work are expected to continue for most of the summer and fall, all work completed by masonry sub-contractors, and overseen by the State of Illinois Capital Development Board (CDB), and Facilities & Services project manager Kevin Price. Read more details about the project here.

Structural improvements to the belltower involve a series of steps that will ultimately produce a seismically stable structure, noted Price.

“The many years of water intrusion on this open, exposed structure have not been kind to this particular portion of Altgeld Hall,” said Price. “When completed, along with the roof replacement work, the Phase 2 work of this CDB project will return the exterior of this iconic UIUC building to its former glory.”

Bailey Edward, an architecture firm in Champaign, is proud to work on this historic renovation, and Karla Smalley, associate principal there, said many options were considered when judging how to clean this stone.

Overly caustic or acidic treatments could ruin the look and integrity of the stone, while very hot water was perhaps not effective enough. High-pressure washing was considered too aggressive, too. Eventually, a relatively basic cleaning technique was established.

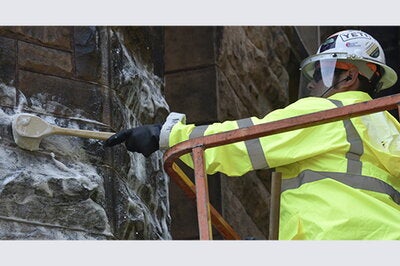

First, wet the stone and its dirt.

Then, a few brushes are used to hand wash and scrub the stone.

Once lathered up with water and the cleaning agent, it’s easy to see as a soap-like liquid. Regular soap it is not, however; it’s a special restoration cleaner used on historic buildings. The soap is washed away, along with dirt and organic material, leaving the stone bright and undamaged.

What’s left is a stone closer to clean than what it’s been in generations.

“Certain deposits stay behind,” said Smalley.

Altgeld was constructed with Hinckley sandstone, a type of stone called a quartz arenite, said Scott D. Elrick, head of the Bedrock Geology Section with the Prairie Research Institute Illinois State Geological Survey.

Hinckley is the assigned name for the sandstone quarried from the Hinckley Formation, a portion of southeastern Minnesota home to tremendous sandstone deposits and an immense below-ground aquifer. Geologic dating of the sandstone dates to the Precambrian age when earth’s early life consisted only of oceanic “soft-bodied creatures like worms and jellyfish,” according to the National Park Service.

“A uniform, compact, well-cemented building stone like the Hinckley is easy to shape, breaks predictably, and is an ‘easy’ material to work with,” said Elrick. “Those are all desirable traits for a construction material.”

Dark green and black coloration was bound to happen, Elrick said. “Once the sandstone was exposed to sunlight and the atmosphere, weathering processes started working away on the exposed surfaces, sunlight being the engine behind algal and biological growth.”

Elrick noted that geologists like him always carry rock hammers to break a rock open and see what’s inside.

“We’re always battling weathering,” Elrick said.

The building will always interact with the atmosphere, water, and biology – so, in time, there will be coloration again at Altgeld.

Travis Tate, U of I Facilities & Services

7-26-23